AICCM talk

A few blog posts ago I promised the text from my short talk at the AICCM conference last year. The first half is below. It is short, and really just the introduction of an idea that needs much more exploration, but here it is! The title: "Do We Need a Theory of the Picture Frame?" Part One.

My name is Anthony Springford, and for most of the last 15 years I have been a lecturer and researcher in Art History and Theory. However about a year ago I decided to start a picture framing business. Like anyone, I have tried to bring my existing skills to bear on the learning of new ones, and so I have been in search of a theoretical discourse to illuminate my current practice of picture framing.

I haven’t found a good book on the topic. If anyone knows of one, please tell me! However in trying to find a theory of picture framing, I have come to realize that my question has been off. I need to start by un-ravelling what I think needs to be theorised, and indeed whether there is a thing there to be theorized. In short: Do we need a theory of the picture frame?

There is a huge amount written around the topic of ‘the frame’ in the abstract; the conceptual work of the frame, the history of frames, or of particular frames. In fact, twentieth century art is, in many ways, a conceptual and aesthetic interrogation of the picture frame and the plinth.

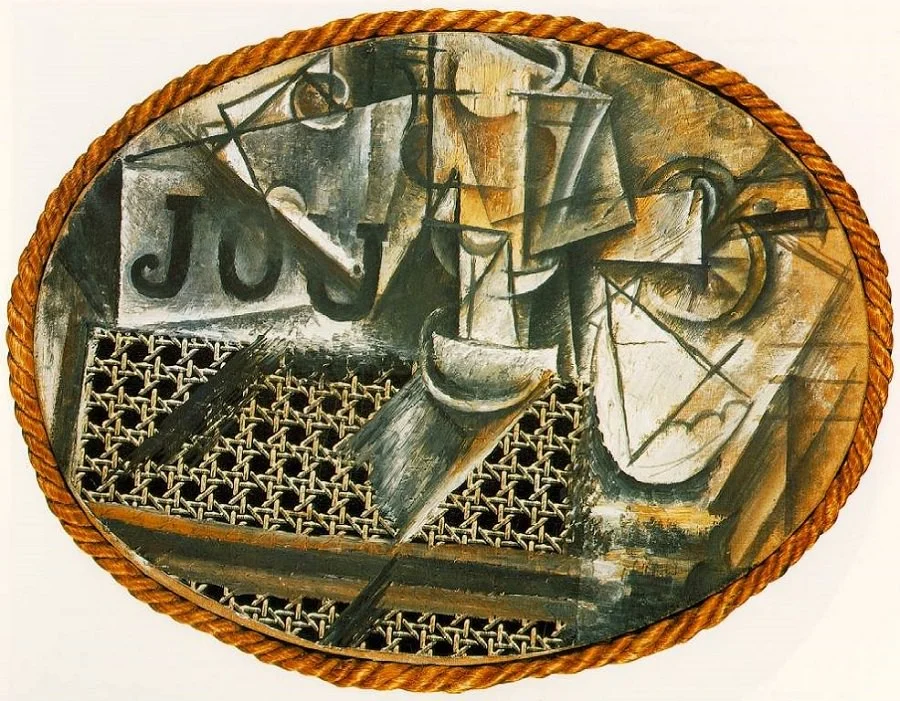

We can trace this examination from Picasso’s fragmentation of the picture frame and its inclusion inside the Cubist painting (as part of the game, and a fragment in a collage, rather than a stable boundary at the limits of the picture plane). Picasso, along with Suerrat, Duchamp, Malevich, make framing a problem artists must deal with.

Eva Hesse’s Hang Up, is basically a frame, from which emerges a giant loop of wire which is given a strange pictorial status because it is anchored to the frame it in a very odd inversion of the Albertian convention of the picture plane as window.

We end up with conceptual art in which the conceptual framing of an experience or action as Art is what is at stake. Robert Barry’s Inert Gas series from 1969. Here, Barry creates an object which is imperceivable (it can’t be seen, felt or smelt) and makes no concrete impact on the world, however the act of documenting it and framing it as art (via the institutions of art, marketing and photography) makes it into this vast and sublime gesture. It becomes a sculpture which encompasses the earth, and which we are all currently breathing. The object is physically unframable, but conversely is constituted only by its institutional framing.

So there is no shortage of theories of the frame, but this tradition addresses the conceptual function of the frame but leaves the frame itself, in an important way, outside the picture.

This is the story of the frame, along with the art object, disappearing, because it addresses the frame, not as a zone of forces and potentialities, but as a conceptual differential between Art and Not-Art. It can be traced to the Kantian concept of Beauty -- which is a concept that serves to frame an experience that cannot be adequately conceptualised -- and Kant’s claim that a good picture frame is self-negating. In other words, the concept of Art defines a cultural space for non-conceptual play and aesthetic judgement, which finds its correlate in the physical picture frame. The picture frame, for Kant, must be kept to a minimum lest it interfere with that space. It should disappear from the experience of the art itself, and, in the history of modern art, it mostly does.

There is another, related reason frames have been pushed to the margin of interpretation. Frames have an intimate relationship to the economic and aesthetic construction of the easel painting, and as a sign of the artwork’s commodity value. A picture frame, in theory at least, is detachable. It belongs to the work on display, but it also belongs to the décor of the room or collection. Frames can change with fashion and with taste, while the work within remains (in principle) unchanged. The frame is sacrificial: it preserves the ideal space of the art work, for as long as it remains supplementary and for as long as we imagine that it contributes nothing meaningful to the work as art.

So in post-modern art discourse, with its insistence on context and politics, the frame is doubly corrupt: first as a sign of the artwork’s aesthetic ideality and secondly as the sign of its emptiness as a commodity. It is why we see plenty of contemporary theorizing of the function of the frame, but very little discussion of the three inches of squiggly stuff at the edge of the picture plane.

Kant uses the Greek Parergon in his 3rd Critique to describe that which sits along-side the work but is not the work itself: the drapery on a figure, the columns on a building, the frame on a picture. Yes, that is a weird bunch of examples, but the notion is that some stuff belongs to the work, marking the artwork off from the world of non-art, and so frames the experience of art as art. Parerga are a supplement, an ornament, that complement the work by being part of the work but not an essential part of the work. If the parerga are insufficiently modest – if they draw attention to themselves through their own fanciness or luxury or artiness – they threaten the work. They become, he says, Schmuck.

At this point, I can’t not mention Derrida’s essay on the Parergon. Not only is it one of the best-known responses to Kant’s comments on the frame, it also gives us tools to imagine the situation differently. While 20th century art has focused on the conceptual framing of art, as art, in true Kantian fashion it has treated the ornamental, material and intimate stuff of the frame as a redundancy, as kitsch, as “schmuck”...